Pre-service teachers’perceptions of creative thinking in an English teacher education program in Chile [1]

Percepciones del profesorado en formación acerca del pensamiento creativo en un programa chileno de pedagogía en inglés

Percepções dos professores em formação sobre o pensamento criativo num programa de formação de professores de inglês no Chile

Jessica Vega-Abarzúa*[2], Max Inostroza*[3], Cristóbal Ruiz*[4], Iván Olivares*[5], Felipe Vásquez*[6]

Universidad Adventista de Chile, Chile*

Fecha de Recepción: 23-8-2025. Fecha de Aceptación: 22-10-2025

Autor de correspondencia: Jessica Vega-Abarzúa, jessicavega@unach.cl

Cómo citar:

Vega-Abarzúa, J.; Inostroza, M.; Ruiz, C.; Olivares, I. y Vásquez, F. (2025). Pre-service teachers’perceptions of creative thinking in an English teacher education program in Chile. Revista Científica Cuadernos de Investigación, 3, e52, 1-17. https://doi.org/10.59758/rcci.2025.3.e52

Abstract

Objective: This study aimed to explore how pre-service teachers of English as a Foreign Language (EFL) perceive creative thinking and the challenges they encounter in fostering it within educational contexts. Methodology: Conducted at a private university in Ñuble, Chile, this small-scale qualitative study involved 12 pre-service teachers enrolled in an English teacher education program. Data were collected through a tailored questionnaire and a semi-structured focus group interview, and analyzed thematically to identify key patterns in participants’ responses. Results: The findings reveal that participants view creative thinking as an essential skill for personal and professional development, primarily cultivated in language arts subjects but also recognized in broader settings such as home, school, and social interactions. Participants also identified barriers to promoting creative thinking in EFL classrooms, including limited conceptual understanding, low confidence, and insufficient pedagogical strategies. Conclusions: The study underscores the importance of explicitly integrating creative thinking into teacher education curricula to strengthen pre-service teachers’ conceptual and practical understanding.

Keywords: creativity; creative thinking; pre-service teachers; teacher education.

Resumen

Objetivo: Este estudio tuvo como propósito explorar cómo los profesores en formación de inglés como lengua extranjera (EFL) perciben el pensamiento creativo y los desafíos que enfrentan al fomentarlo en contextos educativos. Metodología: El estudio, de carácter cualitativo y a pequeña escala, se llevó a cabo en una universidad privada de Ñuble, Chile, y contó con la participación de 12 profesores en formación matriculados en un programa de pedagogía en inglés. Los datos se recopilaron mediante un cuestionario diseñado específicamente para el estudio y una entrevista grupal semiestructurada, y se analizaron temáticamente para identificar patrones clave en las respuestas de los participantes. Resultados: Los hallazgos revelan que los participantes consideran el pensamiento creativo una habilidad esencial para el desarrollo personal y profesional, fomentada principalmente en las asignaturas de lengua y literatura, pero también reconocida en espacios más amplios como el hogar, la escuela y las interacciones sociales. Asimismo, identificaron barreras para promover el pensamiento creativo en el aula de inglés, tales como una comprensión conceptual limitada, baja confianza y escasas estrategias pedagógicas. Conclusiones: El estudio destaca la importancia de integrar explícitamente el pensamiento creativo en los planes de formación docente, con el fin de fortalecer la comprensión conceptual y práctica de los futuros profesores.

Palabras clave: creatividad; pensamiento creativo; profesorado en formación; formación docente.

Resumo

Objetivo: Este estudo teve como objetivo investigar como os professores em formação de inglês como língua estrangeira (EFL) percebem o pensamento criativo e os desafios que enfrentam para promovê-lo em contextos educacionais. Metodologia: Trata-se de um estudo qualitativo de pequena escala, realizado em uma universidade privada de Ñuble, Chile, com a participação de 12 professores em formação matriculados em um programa de licenciatura em inglês. Os dados foram coletados por meio de um questionário elaborado especialmente para o estudo e de uma entrevista em grupo semiestruturada, sendo posteriormente analisados tematicamente para identificar padrões relevantes nas respostas dos participantes. Resultados: Os achados indicam que os participantes consideram o pensamento criativo uma habilidade essencial para o desenvolvimento pessoal e profissional, cultivada principalmente nas disciplinas de artes linguísticas, mas também reconhecida em ambientes mais amplos, como o lar, a escola e as interações sociais. Além disso, foram identificadas barreiras para o estímulo ao pensamento criativo nas aulas de inglês, incluindo compreensão conceitual limitada, baixa autoconfiança e insuficiência de estratégias pedagógicas. Conclusões: O estudo ressalta a importância de integrar explicitamente o pensamento criativo nos currículos de formação docente.

Palavras Chave: criatividade; pensamento criativo; professores em formação; formação de professores.

Introduction

To shed light on English language teacher preparation, this small-scale study explores pre-service teachers’ perceptions of creative thinking. As a cross-curricular competency, creative thinking is considered essential in the education of future teachers. Current teaching standards set by the Chilean Ministry of Education (MINEDUC, 2021) highlight that teacher education programs should foster skills and competencies that enable student teachers to make a meaningful impact on their professional practice. Among these, creative thinking is defined as the capacity to generate or adapt ideas and practices, thereby strengthening the ability to innovate and implement change within the pedagogical field (MINEDUC, 2021).

As an essential cognitive and academic skill, creative thinking has been examined in Chilean undergraduate studies (e.g., Sandoval et al., 2020; Solar, 2003; Troncoso et al., 2022). However, research within teacher education, particularly in the field of English language teaching, remains limited. In light of the recent implementation of new standards for English language teaching, there is a pressing need to expand the body of research that informs and strengthens teacher education programs. This study addresses that need by investigating pre-service teachers’ perspectives on creative thinking, a line of inquiry that can provide deeper insights into their cognitions and their links to classroom practices (Kubanyiova & Feryok, 2015). As Borg (2015) emphasizes, examining teachers’ beliefs is crucial to understanding their decision-making processes and the foundations of their pedagogical choices. Grounded in this perspective, the purpose of this study was to explore English as a Foreign Language (EFL) pre-service teachers’ perceptions of creative thinking.

In educational research, creative thinking has been explored across various disciplines (e.g., Segundo et al., 2020; Ummah et al., 2019). This relevance may be linked to the role of creative thinking in fostering skills essential for academic and professional success, commonly referred to as 21st-century skills. From this 21st-century perspective, creativity and innovation are fundamental abilities for both thinking and interacting (Battelle for Kids, 2019 [previously known as Partnership for 21st Century Learning]). Consequently, it can be argued that creativity is an asset in today’s working and academic life.

Delving deeper into the topic, it becomes necessary to examine the relationship between creativity and creative thinking. While it might be complex to provide a unique definition of creativity, as the concept is both broad and intricate (Meihami, 2022), it is generally agreed that creativity refers to the proposal or generation of new ideas or ways of thinking (Torrance, 1977). Additionally, researchers suggest that creativity is used by human beings to make sense of the world (e.g., Quiroz y Rodríguez, 2017) and requires a socio-cultural environment to stimulate it (García-García et al., 2017; Sandoval, et al., 2020). As a cross-disciplinary ability, creativity must be better understood in relation to the context of each subject area (Baer, 1998) and its characteristics (Jones & Richards, 2015). For instance, Adams (2005) identifies four characteristics of creativity: fluency, flexibility, originality, and novelty which are normally used in gauging creativity. Similarly, Runco & Jaeger (2012) identify originality and effectiveness as fundamental aspects of creativity.

As well as creativity, the literature indicates that creative thinking is a process inherent to every individual. Creative thinking is engaging in cognitive processes to develop something new (Runco & Chand, 1995). Nickerson (1999) identifies specific characteristics in creative thinking, stating that it is “expansive, innovative, inventive and unconstrained” (p. 397). One of the most salient characteristics addressed by the literature about creative thinking is its connection with problem solving (e.g., Muñoz et al., 2021; Torrance, 1977; Ward et al., 1995). In this sense, creative thinking entails looking at and assessing a problem from various perspectives, developing new solutions, and arriving at original cognitive concepts (Hensley, 2020). Another important aspect of creative thinking is its close relationship with critical thinking. Hence, creative and critical thinking are cognitive processes that nurture and complete each other not only in the creation of new ideas but also in evaluating them critically (Fairweather & Cramond, 2010). Based on the conceptualization and characterization of the concepts of creativity and creative thinking, it can be concluded that creative thinking is the mental process that helps individuals generate novel ideas. In other words, creative thinking is the stepping stone to creativity.

Recognizing that creativity can be learned and cultivated (Jónsdóttir, 2017; Kleibeuker et al., 2016; Meller, 2019), educational institutions are increasingly infusing their curricula with 21st-century skills development (Solar, 2003). This 21st-century focus has also permeated teacher education where creative thinking gains special attention (MINEDUC, 2021). In this sense, the National Advisory Committee on Creative and Cultural Education report (NACCCE) (1999) highlights two important aspects that can nurture teacher education: teaching creatively and teaching for creativity. According to the NACCCE report (1999), teaching creatively involves teachers using imaginative approaches to make learning more engaging, stimulating, and effective, whereas teaching for creativity refers to “forms of teaching that are intended to develop young people’s own creative thinking or behavior” (p. 103). These two terms hold special value for teacher education as it is necessary that teachers themselves experience and develop their creative abilities to effectively develop them among their pupils (NACCCE, 1999).

Similarly, researchers Newton & Waugh (2012) underscore the importance of understanding creativity and its implications within the specific discipline being taught in order to provide suitable activities that can effectively promote creative thinking. Based on this, it becomes clear that creative thinking is a complex process that must be initiated in teacher education to effectively be integrated at a school level. Indeed, this integration is intricate, particularly in foreign language instruction (Li, 2016; Read, 2015; Wang & Kokotsaki, 2018) where creativity has not been vastly addressed (Wang & Kokotsaki, 2018) specifically in teacher education. Therefore, understanding how (pre-service) teachers develop their creative abilities and how they integrate them in their practices seems difficult to fully achieve given the limited emphasis on the topic. What is known from empirical research indicates that English as a foreign language (EFL) teachers’ conceptions on creativity seems to be lacking (Wang & Kokotsaki, 2018). For instance, in Masadeh’s (2021) study, EFL teachers did not have a clear understanding of creative thinking. Apart from creating new ideas, teachers struggled to identify other ways to stimulate creativity. Similarly, Wang & Kokotsaki (2018) found that primary school teachers acknowledged the role of creativity in children’s education, yet possessed limited knowledge of its implications and relationship with EFL learning. Wang & Kokotsaki (2018) suggest that EFL teachers may need a framework support model to effectively integrate creativity in the classroom. This aligns with Craft et al. (2014) who assert that creative students require creative educators who can use appropriate strategies to develop creative thinking. Being recognized as a space for active learning and innovative learning experiences resulting from student-centered activities, the EFL classroom becomes the ideal place to display creative ideas (Read, 2015). Therefore, EFL teachers must develop and nurture their own creative abilities to effectively foster and promote creative thinking in their students, as teachers’ beliefs about creativity strongly influence how they cultivate students' creative abilities (Andiliou & Murphy, 2010; Azamalah & Kang, 2023; Makel, 2009; Skiba et al., 2010). Indeed, the literature reveals that while teachers acknowledge the importance of creativity and are aware of its role in students' academic development, the practical implementation of creative teaching strategies is often ill-structured. Makel (2009) describes this phenomenon as the ‘creativity gap,’ where creativity is praised by adults yet minimally cultivated in students. Additionally, the literature suggests that creativity is often associated primarily with the arts (NACCCE, 1999; Newton & Newton, 2014) or relies heavily on arts (Claxton et al., 2006), highlighting the need to understand that creativity can be enhanced through other subject areas (Fisher, 2005; Meller, 2019; NACCCE, 1999).

Based on this context, this study aimed to explore pre-service teachers’ perceptions on creative thinking, focusing on their understanding, experiences and potential challenges they observe in developing creative thinking in the EFL classroom. To meet this end, the following research questions guided the study:

RQ1. What

experiences related to creative thinking do EFL pre-service teachers report?

RQ2. How do EFL pre-service teachers understand creative thinking and

its role in school education?

RQ3. What challenges, if any, do EFL pre-service teachers face when

promoting creative thinking in school education?

Methodology

This study adopted a qualitative approach, as it sought to understand a phenomenon from the perspectives of those directly involved (Creswell & Creswell, 2023). Specifically, the study aimed to explore how EFL pre-service teachers perceive creative thinking. By focusing on participants’ voices and lived experiences, the study sought to provide nuanced insights that can inform both research and practice.

The study focused on EFL pre-service teachers, and the sample consisted of 12 late-stage participants, including six in their fourth year of teacher training (Group A) and six in their fifth year (Group B). All participants were enrolled in an English teacher education program at a private university in Ñuble, Chile. Their participation in the study was voluntary, and purposive sampling was employed to ensure that participants were directly connected to the phenomenon under investigation, where the inclusion criteria defined: (i) enrollment in an English teacher education program, and (ii) being in the fourth or fifth year of study, as this ensured prior practicum experience. This requirement was particularly important, as pre-service teachers with classroom exposure are better positioned to reflect on how creative thinking connects to teaching practices. Participants were excluded if they did not complete the questionnaire that preceded the focus group.

Data were collected through a tailored digital questionnaire and a focus group conducted at the research site. The questionnaire was designed to capture participants’ general experiences with creative thinking specifically in the dimensions of school, higher education, and family/social groups. Likewise, the questionnaire served as the basis for developing guiding questions for the focus group, which encouraged participants to reflect more deeply on their beliefs and practices. To enhance validity and reduce bias, both instruments were peer-reviewed by two academic researchers in English language education. Their review assessed the alignment of the questions with the study’s construct and objectives, as well as the clarity and appropriateness of the language for the participant group. Based on their feedback, adjustments were made to improve wording and ensure coherence.

Ethical considerations were addressed throughout the study. Prior to implementation, the research protocol was reviewed and approved by an institutional ethics committee. Following this approval, participants were informed about the purpose of the study, the role of the researchers, and the anonymity and confidentiality of their participation. Informed consent was obtained prior to each instance of data collection, and participants were reminded that their involvement was voluntary and that they could withdraw at any time without consequence.

Data were analyzed thematically, following the procedures outlined by Creswell and Creswell (2023). This involved iterative reading, coding, and categorizing of the data to identify emerging themes related to pre-service teachers’ perceptions of creative thinking. Data from the digital questionnaire were organized into a spreadsheet and categorized manually and presented by frequencies, as the volume of responses was not extensive. On the other hand, focus group data were firstly transcribed verbatim from audio recordings and later refined to ensure clarity and accuracy in representing participants’ responses. To facilitate its analysis, ATLAS.ti (version 23) was employed to support systematic coding and data management. Researchers manually assigned codes to significant excerpts across transcripts, which were then grouped into three overarching research questions of the study which included: experiences, understandings, and challenges. Within ATLAS.ti, codes were color-coded to visually differentiate subthemes and track their recurrence across participants’ responses. The software also enabled the development of thematic networks and the alignment of codes with illustrative quotations, thereby enhancing the transparency and rigor of the analysis.

To ensure trustworthiness, the study incorporated peer debriefing strategies, drawing on Creswell and Creswell (2023). An external researcher reviewed the proposal and discussed methodological aspects with the research team to enhance clarity. In addition, a cross-checking technique was applied throughout the analysis. This ensured that coding decisions and thematic development were discussed among the research team to minimize individual bias.

Results

The findings are presented in relation to the research questions guiding the study. To capture further nuances, results are also reported according to participants’ stage of training, distinguishing between Group A (fourth-year) and Group B (fifth-year) pre-service teachers.

RQ1. What experiences related to creative thinking do EFL pre-service teachers report?

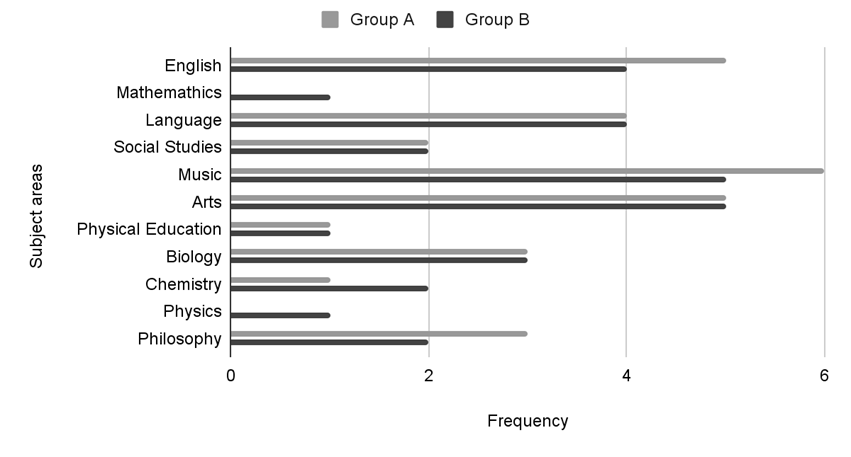

This research question was examined across three dimensions addressed in the questionnaire: school, higher education, and family/social groups. Regarding school experiences, participants were asked: Based on your opinion and school experience, which subjects most develop creative thinking? Both groups reported a strong association between creative thinking and the subjects of music, arts, and English. Conversely, mathematics and physics were perceived as subjects that foster creative thinking to a much lesser extent.

Figure 1. Perceived development of creative thinking across subject areas. Personal elaboration.

The school dimension was also explored through the question: Based on your opinion and school experience, how was creative thinking relevant in the English subject? Participants’ answers identified two main themes shared by both Group A and Group B. Creative thinking is key: 8 out of 12 participants mentioned that creative thinking is fundamental to school education, specifically in English language learning. Lack of encouragement: 5 participants mentioned that they believe that creative thinking was not openly encouraged in the English subject, and other 4 participants expressed that English learning activities entailed being creative to some extent.

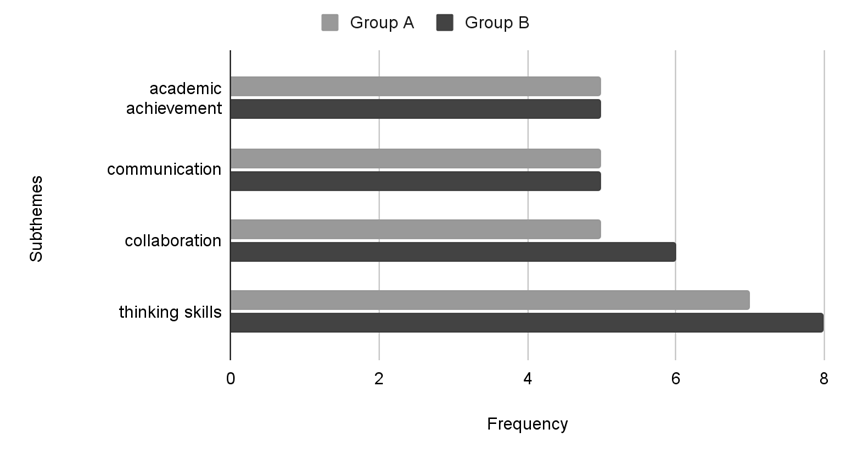

The higher education dimension included the question: Based on your opinion and teacher education experience, how is creative thinking relevant in your ELT program? Overall, all participants acknowledged the importance of creative thinking in their ELT program. As shown in Figure 2, their responses centered on four main themes, indicating that creative thinking was perceived as particularly relevant for their academic achievement, communication, collaboration, and thinking skills. Group B, in particular, placed slightly greater emphasis on collaboration and thinking skills.

Figure 2. Perceived importance of creative thinking in the ELT program. Personal elaboration.

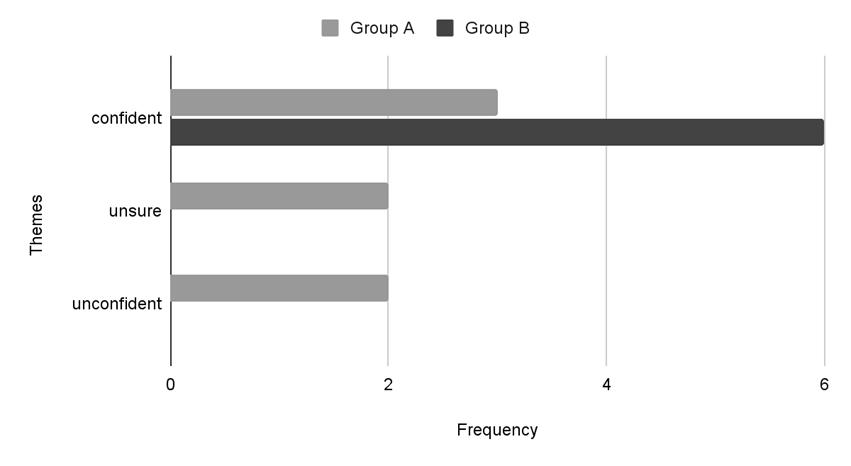

When asked about their feelings toward promoting creative thinking in the English classroom, three main themes emerged, as illustrated in Figure 3. Participants’ responses suggest that Group B demonstrated greater confidence in their readiness to foster creative thinking, whereas Group A’s responses were characterized by expressions of uncertainty and lack of confidence.

Figure 3. Perceived confidence to promote creative thinking. Personal elaboration.

In the third dimension of the questionnaire, participants were asked about the role of family and social groups in fostering creative thinking. All participants agreed that the family should serve as the central institution for promoting creativity. However, 5 out of 12 acknowledged that creative thinking was not explicitly encouraged at home. Interestingly, all participants considered that creative thinking was primarily stimulated through social groups such as conventions, fandoms, friendships, and social media.

RQ2. How do EFL pre-service teachers understand creative thinking and its role in school education?

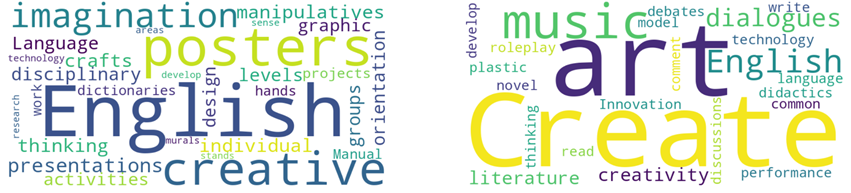

This research question was examined through focus group data. When asked about their views on creative thinking, participants shared various opinions and words associated with the concept, which were represented in a word cloud (see Figure 4). The word cloud for Group A highlighted terms such as English, posters, creative, and imagination, while Group B emphasized create, art, music, and English. These perspectives aligned with the questionnaire findings, as participants generally associated creative thinking with skills connected to language arts subject areas.

Group A Group B

Figure 4. Participants’ views on creative thinking as represented in a word cloud. Personal elaboration.

The second question in the focus group explored how creative thinking is developed or stimulated. Participants expressed that it can be fostered in various contexts and through multiple approaches, with many highlighting the home as a key institution. As one participant noted: “Creative thinking should be developed at home since parents bring up their children in a very narrow-thinking environment, then it would be difficult to change that at school” (Participant 2).

While participants emphasized the importance of the family, several also acknowledged that, due to the socioeconomic and sociocultural characteristics of many households, schools should take on a central role in fostering creativity. Primary education, in particular, was regarded as crucial: “It [creative thinking] is stimulated in different contexts, but of these, primary education makes the difference because maybe not all families know or are really present in the education of their children” (Participant 8).

Interestingly, despite these views, participants commonly reflected that their own creative thinking had been promoted primarily through their university experience. As one participant explained: “Personally, I believe that creative thinking was mainly developed here [teaching program] through the types of activities and assignments because I do not recall that it [creative thinking] was stimulated at school level” (Participant 4).

A second question addressed in the focus group concerned the role of creative thinking in the English language classroom. From participants’ responses, three themes were identified across both groups (see Table 2). The first theme, problem solving and practical application, reflects participants’ views of creative thinking as a pivotal skill for addressing challenges and managing everyday situations. Supporting quotes illustrate this perspective, such as:

I believe that creative thinking takes place when you are given a task to solve, a project or something like that in which you use creative thinking and creativity. This can be in day to day life, in some activity or when you plan the activity for your students to use their creative thinking” (Participant 7). Creative thinking can enhance problem-solving and cultural diversity understanding” (Participant 8).

The second theme identified was the belief that creative thinking in the EFL classroom is closely linked to technology and innovation. As Participant 1 explained: “Creativity and creative thinking are essential for innovation in teaching methods to reach students effectively. In that way we avoid traditional and outdated methodologies”.

The third theme, driver for language learning, emerged across both groups. Participants emphasized that, beyond facilitating the learning of English, creative thinking is a fundamental skill for understanding and engaging with the language more deeply.

“A creative mindset opens up the mind to learning new languages and all that it encompasses” (Participant 10).

“I believe that one can always continue to develop creativity. Creativity is crucial for leveraging English as a tool for personal and professional growth”(Participant 2).

RQ3. What challenges, if any, do EFL pre-service teachers face when promoting creative thinking in school education?

To address this research question, participants were asked during the focus group whether they anticipated any challenges in promoting creative thinking in their future teaching experiences. Analysis of their responses revealed three main challenges, which are summarized in Table 1. Both groups acknowledged the difficulties of fostering creative thinking in the EFL classroom.

The first challenge, common to both groups, was a lack of formal understanding and confidence. Participants expressed uncertainty and confusion about what creative thinking entails, which appeared to hinder their ability to promote it consciously in the classroom. This lack of understanding also contributed to feelings of insecurity, compounded by personal perceptions of not being inherently creative, as illustrated by the supporting quotes in Table 1.

The second major challenge was adapting teaching approaches and materials. While participants in both groups recognized the importance of tailoring instructional resources and teaching methods to meet learners’ needs, they expressed uncertainty about how to effectively foster creative thinking. Participants emphasized that promoting creative thinking involves engaging with learning experiences in which the skill can be deliberately practiced and developed within their teacher education program.

The third challenge involved the perceived value of creative thinking in schools and teacher education. Responses from both groups indicated awareness of its importance in the EFL classroom, yet participants identified structural and pedagogical barriers that hinder its full integration. Group A, in particular, perceived creative thinking as often overlooked and underutilized, with limited opportunities to promote it. Likewise, Group B suggested that the teaching of creative thinking should be explicitly and intentionally incorporated into teacher education programs.

Table 1. Perceived challenges of promoting creative thinking in school education.

|

Themes |

Group A |

Group B |

|

|

Lack of understanding and confidence |

“Am I prepared to promote creative thinking in my future students? I don't think so, not now at least" (Participant 8).

"I agree with Participant 7. Some games are for learning and some are designed to promote creative thinking, but I can not identify which is which" (Participant 9).

"Sometimes I feel prepared [to promote creative thinking] and sometimes not” (Participant 10). |

"At least I don't feel very prepared because I still don't fully understand the concept of what creative thinking is. Maybe I can use it unconsciously, but not promote it" (Participant 1).

“I still don't feel prepared to promote it. I don't consider myself a creative person" (Participant 4).

“I feel the same as Participant 1, plus, I feel it's also a personal limitation of mine, that I'm not very creative" (Participant 5). |

|

|

Adapting teaching approach and materials |

"In my case, it happened during a practicum. I tried to be creative, I prepared different activities, things like that, and I had a student with special needs that was not being addressed, so I gave him what I thought he needed, but he didn't engage, so that led me to also doubting my abilities. I even gave him drawings and everything to engage him and tried to incorporate him into the subject, but he just wanted to play with the scissors. Besides, we as future teachers must also be taught with more materials such as cards or games I think. Classes tend to be very traditional” (Participant 6).

|

“Learn through creativity to avoid traditional and outdated methodologies” (Participant 1).

"Well I’m not really sure but, in my case, I think the way I would promote it [creative thinking] is by collecting data: what the students' interests are, what they like to do... collecting all that information and adapting the instruction to them" (Participant 3).

|

|

|

Overlooked skill |

“The potential for creativity is often unfulfilled, lacking meaningful integration with learning objectives… Creativity is underutilized in Chilean education, often lacking connection between activities and learning aims” (Participant 9). |

“Although creative thinking and creativity are recurring topics in our teaching program, they need to be explicitly addressed to promote them correctly” (Participant 1). |

Personal elaboration.

Discussion

This study examined EFL pre-service teachers’ perceptions of creative thinking. By addressing three research questions through a questionnaire and a focus group, it shed light on their experiences, understandings, and perceived challenges related to creative thinking and its role in school education.

Regarding participants’ experiences, the findings indicate that creative thinking was perceived as an essential skill cultivated across different contexts, including school, higher education, and family/social groups. While pre-service teachers acknowledged that it would be ideal for creative thinking to be nurtured at home, they also recognized that socioeconomic and sociocultural disparities may limit such opportunities. Consequently, they emphasized the pivotal role of school education in fostering creative thinking, noting that, in their own case, this skill was primarily developed during their higher education studies. This reflection carries significant implications for teacher preparation. In line with current ELT teaching standards, future teachers are expected to cultivate 21st-century skills that support both academic achievement and life success (MINEDUC, 2021). Moreover, the fact that pre-service teachers considered sociocultural contexts and learner diversity as central elements is a noteworthy finding, as such awareness is fundamental for designing learning activities that foster communicative competence in their future classrooms (MINEDUC, 2021).

In terms of creative thinking and its role in school education, most EFL pre-service teachers understood creative thinking as being cultivated primarily within language arts subjects, rather than as a cross-curricular competence. This finding was consistent across both stages of data collection. Viewing creative thinking as confined to only a limited number of subject areas may reflect a misconception (NACCCE, 1999; Newton & Newton, 2014). Such misconceptions, or gaps in knowledge about essential skills, need to be explicitly addressed in teacher education programs if meaningful impacts are to be achieved in school classrooms (Wang & Kokotsaki, 2018). Therefore, it is essential that English teacher education programs emphasize that the role of the English classroom extends beyond developing linguistic proficiency to fostering broader life skills, including critical thinking, creative thinking, communication, and collaboration, as highlighted in the current teaching standards (MINEDUC, 2021).

Regarding the challenges of promoting creative thinking in the EFL classroom, participants expressed concerns about how to effectively develop this skill. This finding highlights a disconnect between theory and practice as participants recognized the significant role of creative thinking as it may facilitate language learning. However, they struggled with how to develop and integrate it into classroom instruction. A key reflection was their acknowledgment of a lack of understanding of the concept and its implications, which contributes to their feelings of insecurity. This perceived difficulty suggests a need for a more holistic educational experience that enables pre-service teachers to not only engage with the theoretical aspects of teaching but also understand how these theories impact and permeate classroom practices (Hammond, 2024; MINEDUC, 2021). Holmquist (2019) emphasizes the importance of pairing abstract concepts related to teaching with real classroom experiences, as these are the ones that teacher candidates tend to value the most. Knowledge limitations in teacher training can impact the praxis of teachers as they are forced to fill the missing gaps through their own experiences (Azamalah & Kang, 2023).

Another challenge that across participants' answers was connected to adapting the teaching approach and materials. Participants are aware that promoting creative thinking may require using different teaching methods and strategies as well as adapting teaching materials to specific educational contexts and individual student needs. These views align with theoretical perspectives (e.g., Harmer, 2015; Díaz-Rico, 2019; Wright, 2019), which argue that English language teaching should incorporate diverse instructional resources and learning opportunities. Similarly, research (e.g., Vega-Abarzúa et al., 2024) emphasizes that adapting teaching materials to learners' contexts has the potential to benefit both teachers and students.

The third perceived challenge in promoting creative thinking in the EFL classroom relates to the value assigned to creative thinking, which participants believe extends from schools to teacher education programs. Participants expressed that creative thinking is not fully appreciated, lacking effective integration in the classroom, and that they require more guidance on their teaching program to foster such thinking processes. Based on this, it is possible to conclude that participants’ understanding of creative thinking was primarily derived from personal experiences rather than formal education. This finding aligns with prior research (e.g., Azamalah & Kang, 2023; Li, 2016; Masadeh, 2021), which suggests that teacher education programs need to engage student teachers in deeper and more explicit learning processes, particularly in the competencies and skills required of 21st-century educators (Li, 2023). These perspectives support the idea of enriching teacher education with a comprehensive foundation that promotes deep learning and offers diverse opportunities for applying teaching in varied contexts (Bland et al., 2023). Moreover, it is crucial to enhance pre-service teachers' academic training with learning experiences that can be replicated in their future practice (NACCCE, 1999; Holmquist, 2019).

Future research could explore the relationship between (pre-service) teachers' creative thinking and strategies for developing these crucial skills in the classroom, particularly in EFL teaching, where the integration of creativity is still evolving (Li, 2016). In the same line, future studies may further probe into the relationship between creative thinking and teaching strategies and/or instructional materials.

Conclusion

The findings of this small-scale study shed light on the multifaceted nature of creative thinking and its important role across disciplines and educational levels. In the context of ELT, it is crucial that English teacher education programs equip future teachers with both the theoretical knowledge and practical strategies needed to confidently foster creative thinking in their classrooms. This includes helping pre-service teachers understand the concept of creativity, recognize its cross-curricular relevance, and develop skills to implement it effectively in diverse learning contexts.

It is important to note that this study was limited to a small sample of participants, and its findings may be context-specific, reflecting the particular experiences and educational environments of these pre-service teachers. Future research could expand the sample size, include multiple institutions, or explore longitudinal impacts to provide a more comprehensive understanding of how creative thinking is perceived and cultivated in teacher education.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to acknowledge the time and valuable participation of the pre-service teachers who contributed to this study.

Conflict of interests

The authors of this study declare no conflicts of interest.

References

Adams, K. (2005). The Sources of innovation and creativity. National Center on Education and the Economy (NJ1). https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED522111

Andiliou, A. & Murphy, K. P. (2010). Examining variations among researchers’ and teachers’ conceptualizations of creativity: A review and synthesis of contemporary research. Educational Research Review, 5(3), 201–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2010.07.003

Azamalah, V. & Kang, N. (2023). Teachers’ perceptions of creativity and teaching: A comparison of African and South Korean teachers. Innovation and Education, 5(1), 32-53. https://doi.org/10.1163/25248502-2023xx01

Baer, J. (1998). The case for domain specificity of creativity. Creativity Research Journal, 11(2), 173–177. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326934crj1102_7

Battelle for Kids (2019). Framework for 21st century definitions. https://www.battelleforkids.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/P21_Framework_DefinitionsBFK.pdf

Bland, J. A.; Wojcikiewicz, S. K.; Darling-Hammond, L. & Wei, W. (2023). Strengthening pathways into the teaching profession in Texas: Challenges and opportunities. Learning Policy Institute. https://doi.org/10.54300/957.902

Borg, S. (2015). Teacher cognition and language education: Research and practice. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Claxton, G.; Edwards, L. & Scale-Constantinou, V. (2006). Cultivating creative mentalities: A framework for education. Thinking skills and creativity, 1(1), 57-61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2005.11.001

Craft, A.; Hall, E. & Costello, R. (2014). Passion: Engine of creative teaching in an English university? Thinking Skills and Creativity, 13, 91–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2014.03.003

Creswell, J. W. & Creswell, J. D. (2023). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (6th ed.). SAGE Publications.

Fairweather, E. & Cramond, B. (2010). Infusing creative and critical thinking into the curriculum together. In: R. A. Beghetto & J. C. Kaufman (Eds.). Nurturing creativity in the classroom (pp. 113–141). Cambridge University Press.

Fisher, R. (2005). Teaching children to think. Nelson Thornes.

García-García, J. J.; Parada-Moreno, N. J. & Ossa-Montoya, A. F. (2017). El drama creativo una herramienta para la formación cognitiva, afectiva, social y académica de estudiantes y docentes. Revista Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales, Niñez y Juventud, 15(2), 839–859. https://doi.org/10.11600/1692715x.1520430082016

Darling-Hammond, L. (2024). Reinventing Systems for Equity. ECNU Review of Education, 7(2), 214-229. https://doi.org/10.1177/20965311241237238

Díaz-Rico, L. T. (2019). A course for teaching English learners (3rd ed.). Pearson.

Harmer, J. (2015). The practice of English language teaching (5th ed.). Pearson Education Limited.

Hensley, N. (2020). Educating for sustainable development: Cultivating creativity through mindfulness. Journal of Cleaner Production, 243, 118542. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.118542

Holmquist, M. (2019). Lack of qualified teachers: A global challenge for future knowledge development. In: R. B. Monyai (ED.). Teacher education in the 21st century (pp. 53-66). IntechOpen.

Jones, R. H. & Richards, J. C. (2015). Creativity and language teaching. In: R. H. Jones & J. C. Richards (Eds.). Creativity in language teaching: Perspectives from research and practice (pp. 3–15). Routledge.

Jónsdóttir, S. R. (2017). Narratives of creativity: How eight teachers on four school levels integrate creativity into teaching and learning. Thinking skills and creativity, 24, 127-139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2017.02.008

Kleibeuker, S. W.; De Dreu, C. K. & Crone E. A. (2016). Creativity development in adolescence: Insight from behavior, brain, and training studies. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 151, 73–84. https://doi.org/10.1002/cad.20148

Kubanyiova, M. & Feryok, A. (2015). Language teacher cognition in applied linguistics research: Revisiting the territory, redrawing the boundaries, reclaiming the relevance. The Modern Language Journal, 99(3), 435-449. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12239

Li, L. (2016). Integrating thinking skills in foreign language learning: What can we learn from teachers’ perspectives? Thinking Skills and Creativity, 22, 273–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2016.09.008

Li, L. (2023). Critical thinking from the ground up: teachers’ conceptions and practice in EFL classrooms. Teachers and Teaching, 29(6), 571-593. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2023.2191182

Makel, M. C. (2009). Help us creativity researchers, you're our only hope. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 3(1), 38–42. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014919

Masadeh, T. S. Y. (2021). Teaching practices of EFL teachers and the enhancement of creative thinking skills among learners. International Journal of Asian Education, 2(2), 153–166. https://doi.org/10.46966/ijae.v2i2.173

Meihami, H. (2022). An exploratory investigation into EFL teacher educators’ approaches to develop EFL teachers’ ability to teach for creativity. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 43,101006. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2022.101006

Meller, P. (2019). Claves para la educación del futuro: Creatividad y pensamiento crítico. Catalonia Ltda.

Ministry of Education (2021). Estándares de la profesión docente. Carreras de Pedagogía en Inglés. Educación Básica/Media. Centro de perfeccionamiento, experimentación e investigaciones pedagógicas (CPEIP). https://estandaresdocentes.mineduc.cl/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/ingles.pdf

Muñoz S., F. D.; Luna G., J. R. & López R., O. (2021). El pensamiento creativo en el contexto educativo. Revista Científica de la UCSA, 8(3), 39-50. https://doi.org/10.18004/ucsa/2409-8752/2021.008.03.039

National Advisory Committee on Creative and Cultural Education (1999). All our futures: Creativity, culture and education. National Advisory Committee on Creative and Cultural Education. https://www.creativitycultureeducation.org/publication/all-our-futures-creativity-culture-and-education/

Newton, L. & Waugh, D. (2012). Creativity in English. In L. Newton (Ed.). Creativity for a new curriculum (pp. 19-35). Routledge.

Newton, L. D. & Newton, D. P. (2014). Creativity in 21st-century education. Prospects, 44(4), 575–589. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11125-014-9322-1

Nickerson, R. S. (1999). Enhancing creativity. In: R. J. Sternberg (Ed.). Handbook of creativity (pp. 392–430). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511807916.022

Quiroz S., M. y Rodríguez M., M. (2017). Reflexiones en torno a la creatividad al servicio de la persona visto desde la experiencia de la carrera de Diseño. Dilemas Contemporáneos: Educación, Política y Valores, 4(2), 11. https://dilemascontemporaneoseducacionpoliticayvalores.com/index.php/dilemas/article/view/210

Read, C. (2015). Seven pillars of creativity in primary ELT. In: A. Maley, & N. Peachey (Eds.). Creativity in the English language classroom (pp. 29-36). British Council.

Runco, M. A. & Chand, I. (1995). Cognition and creativity. Educational Psychology Review, 7(3), 243–267. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02213373

Runco, M. A. & Jaeger, G. J. (2012). The Standard Definition of Creativity. Creativity Research Journal, 24(1), 92–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2012.650092

Sandoval O., E.; Toro A., S.; Poblete G., C. & Moreno D., A. (2020). Socio-educational implications of creativity from pedagogical mediation: A critical review. Estudios Pedagógicos (Valdivia), 46(1), 383-397. https://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0718-07052020000100383

Segundo M., R. I.; López F., V.; Daza G., M. T. & Phillips-Silver, J. (2020). Promoting children’s creative thinking through reading and writing in a cooperative learning classroom. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 36, 100663. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2020.100663

Skiba, T.; Tan, M.; Sternberg, R. J. & Grigorenko, E. L. (2010). Roads not taken, new roads to take: Looking for creativity in the classroom. In: R. A. Beghetto & J. C. Kaufman (Eds.). Nurturing creativity in the classroom (pp. 252–269). Cambridge University Press.

Solar, M. I. (2003). Creatividad en el ámbito universitario: la experiencia de Chile. Creatividad y Sociedad, 3, 39-45. http://creatividadysociedad.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/revista-CS-3.pdf#page=35

Torrance, E. P. (1977). Educación y capacidad creativa. Ediciones Morova.

Troncoso, A.; Aguayo, G.; Acuña, C. C. y Torres, L. (2022). Creatividad, innovación pedagógica y educativa: Análisis de la percepción de un grupo de docentes chilenos. Educação e Pesquisa, 48. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1678-4634202248238562

Ummah, S. K.; In’am, A. & Azmi, R. D. (2019). Creating manipulatives: Improving students’ creativity through project-based learning. Journal on Mathematics Education, 10(1), 93–102. https://doi.org/10.22342/jme.10.1.5093.93-102

Vega-Abarzúa, J.; Guerra B., V. & Benavente R., C. (2024). Developing a contextualized card game to enhance productive skills in the English as a foreign language classroom. Revista Científica Cuadernos de Investigación, 2(30), 1-12. https://cuadernosdeinvestigacion.unach.cl/index.php/rcci/article/view/e30

Wang, H.C. (2019). Fostering learner creativity in the English L2 classroom: Application of the creative problem-solving model. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 31, 58–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2018.11.005

Wang, L. & Kokotsaki, D. (2018). Primary school teachers’ conceptions of creativity in teaching English as a foreign language (EFL) in China. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 29, 115–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2018.06.002

Ward, T. B.; Finke, R. A. & Smith, S. M. (1995). Creativity and the mind: Discovering the genius within. Plenum Press. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-3330-0

Wright, W. E. (2019). Foundations for teaching English language learners: Research, theory, policy, and practice (3rd ed.). Caslon Publishing.