Developing a contextualized card game to enhance productive skills in the English as a foreign language classroom[1]

Elaboración de un juego de cartas contextualizado para mejorar habilidades productivas en la asignatura de inglés como lengua extranjera

Elaboração de um jogo de cartas contextualizado para aprimorar habilidades produtivas na atribuição de inglês como língua estrangeira

Jessica Vega-Abarzúa

Universidad Adventista de Chile

![]() https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5260-5584

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5260-5584

Valeria Guerra Budini

![]() Universidad

Adventista de Chile

Universidad

Adventista de Chile

https://orcid.org/0009-0003-8217-9699

Camila Benavente Rubio

Universidad Adventista de Chile

![]() https://orcid.org/0009-0005-5776-9587

https://orcid.org/0009-0005-5776-9587

Recibido: 23-02-2024

Aceptado: 30-04-2024

Cómo citar este documento:

Vega-Abarzúa, J.; Guerra B., V. & Benavente R., C. (2024). Developing a contextualized card game to enhance productive skills in the English as a foreign language classroom. Revista Científica Cuadernos de Investigación, 2, e30, 1-12. https://cuadernosdeinvestigacion.unach.cl/index.php/rcci/article/view/e30

Abstract

Aim: This study outlines the development of a contextualized card game aimed at enhancing productive skills for English as a foreign language (EFL) students in Ñuble, Chile. Recognizing the importance of contextualization in language learning, the researchers designed a game centered around iconic places of Ñuble to address the challenges of accessing meaningful language-learning materials. Methodology: The process was developed in four distinct phases: planning, curricular alignment, designing, and socialization. Each phase contributed to refining the instructional material, culminating in a set of 14 cards. These cards served as an avenue to explore the insights from three groups of participants – learners, teachers, and academics – and to identify the game's effectiveness in enhancing productive skills. Results: Findings indicate positive appraisals on the game's contextualization, showing a potential to motivate learners towards English language learning. Participants also recognized the game's flexible use in the EFL classroom and acknowledged its effectiveness in strengthening oral and written tasks. Conclusion: This initiative represents an innovative approach to leveraging local contexts for engaging language learning tools. Future research can build upon these findings to explore the effects of similar instructional materials in diverse educational settings.

Keywords: contextualization; game-based learning; pedagogical resources; language-learning materials.

Resumen

Objetivo: Este estudio describe el desarrollo de un juego de cartas contextualizado destinado a mejorar las habilidades productivas de los estudiantes de inglés como lengua extranjera (EFL) en Ñuble, Chile. Al reconocer la importancia de la contextualización en el aprendizaje de idiomas, los investigadores diseñaron un juego centrado en lugares icónicos de Ñuble para abordar los desafíos de acceder a materiales significativos para el aprendizaje de idiomas. Metodología: El proceso de desarrollo se desarrolló en cuatro fases distintas: planificación, alineación curricular, diseño y difusión. Cada fase contribuyó a perfeccionar el material didáctico, culminando en un conjunto de 14 cartas. Éstas sirvieron como vía para explorar las ideas de tres grupos de participantes (estudiantes, profesores y académicos) e identificar la eficacia del juego para mejorar las habilidades productivas. Resultados: Los hallazgos indican valoraciones positivas sobre la contextualización del juego, mostrando un potencial para motivar a los estudiantes hacia el aprendizaje del idioma inglés. Los participantes también reconocieron el uso flexible del juego en el aula de inglés como lengua extranjera y reconocieron su eficacia para fortalecer las tareas orales y escritas. Conclusión: Esta iniciativa representa un enfoque innovador para aprovechar los contextos locales para generar herramientas atractivas para el aprendizaje de idiomas. Investigaciones futuras pueden aprovechar estos hallazgos para explorar los efectos de materiales educativos similares en diversos entornos educativos.

Palabras clave: contextualización; aprendizaje basado en juegos; recursos pedagógicos; materiales para el aprendizaje de idiomas.

Resumo

Objetivo: Este estudo descreve o desenvolvimento de um jogo de cartas contextualizado com o objetivo de melhorar as habilidades produtivas de estudantes de inglês como língua estrangeira (EFL) em Ñuble, Chile. Reconhecendo a importância da contextualização na aprendizagem de línguas, os investigadores conceberam um jogo centrado em locais icónicos de Ñuble para enfrentar os desafios de acesso a materiais significativos de aprendizagem de línguas. Metodologia: O processo de desenvolvimento se desdobrou em quatro fases distintas: planejamento, alinhamento curricular, concepção e compartilhamento. Cada fase contribuiu para o refinamento do material instrucional, culminando em um conjunto de 14 cartas. Estes cartões serviram como um meio para explorar as ideias de três grupos de participantes – alunos, professores e académicos – e para identificar a eficácia do jogo na melhoria das competências produtivas. Resultados: Os resultados indicam avaliações positivas sobre a contextualização do jogo, mostrando potencial para motivar os alunos para a aprendizagem da língua inglesa. Os participantes também reconheceram o uso flexível do jogo na sala de aula de EFL e reconheceram a sua eficácia no fortalecimento de tarefas orais e escritas. Conclusão: Esta iniciativa representa uma abordagem inovadora para aproveitar os contextos locais para envolver ferramentas de aprendizagem de línguas. Pesquisas futuras podem aproveitar essas descobertas para explorar os efeitos de materiais instrucionais semelhantes em diversos ambientes educacionais.

Palavras-chave: contextualização; aprendizagem baseada em jogos; recursos pedagógicos; materiais de aprendizagem de línguas.

Introduction

Undoubtedly, contextualization is a fundamental concept intertwined with language teaching and learning as it facilitates a deeper understanding of language by connecting it to real-world situations. Broadly defined, contextualization involves presenting language-learning materials and activities in meaningful and authentic contexts that mirror real-life situations (Ellis, 1994). The umbrella term contextualization encompasses various related terms such as contextualized instruction (Rivet & Krajcik, 2007; Roberts, et al., 2020), contextual teaching and learning (Baker, et al., 2009; Johnson, 2002), and functional context education (Sticht, 2000), among others. To guide our study, we adopt the perspectives put forth by Mazzeo (2008), who define contextualization as “A diverse family of instructional strategies designed to more seamlessly link the learning of foundational skills and academic or occupational content by focusing teaching and learning squarely on concrete applications in a specific context” (pp. 3-4). These purposeful actions prove beneficial for connecting language use to relevant situations, settings, and cultural aspects in English language settings (Larsen-Freeman, 2011). Numerous studies highlight the advantages of contextualized learning, with motivation emerging as a prominent finding in EFL research (e.g., Chen et al., 2019; Chen et al., 2022). According to Chen et al. (2019), contextualization not only facilitates language acquisition but also triggers high levels of motivation among EFL learners. Additional research (e.g., Chen & Wright, 2017; Zoghi & Mirzaei, 2014) demonstrates that employing contextualization as a method for selecting and adapting teaching materials positively influences learners. This approach helps them use language in relevant contexts, comprehend the purpose, function, and nuances of the language, thereby enhancing the meaningfulness of the learning experience.

Contextualization in the English curriculum

In Chile, the pedagogical framework for English Language Teaching (ELT) within the school curriculum is guided by a constructivist approach. Thus, educators are encouraged to foster a student-centered environment, promoting active learning through self-directed exploration and collaborative efforts (Ministerio de Educación, MINEDUC, 2016). Under this view, the English curriculum is based on a communicative appraisal of the language wherein interaction becomes the ultimate goal, aligning with the crucial components of 21st-century learning (Partnership 21, 2015). Rooted in this communicative approach, the curriculum emphasizes the pivotal role of contextualization in its implementation in two main areas. In a didactic sphere, the English curriculum asserts that contextualization should serve as a means to facilitate communication in real-life scenarios (MINEDUC, 2016). Moreover, these curricular orientations underscore the importance of contextualization when addressing lexical and grammatical aspects to foster communicative competence. For example, in grammar teaching, it is recommended to follow an inductive approach, allowing learners to decipher patterns and structures of the language. According to the curriculum, contextualization is fundamental in this process, as teachers should resort to examples, activities, and resources that are relevant to the students' reality (MINEDUC, 2016).

It is noteworthy that contextualization not only influences the didactic processes of English Language Teaching (ELT) but also extends its impact to a critical domain – assessment. In this domain, Language assessment emphasizes identifying the linguistic abilities of students and their performance in authentic communication, considering contextualization. To achieve this objective, the curriculum underscores a diverse range of assessment types, encompassing traditional methods such as written exams, as well as innovative forms like posters, plays, graphic organizers, and drawings, among others. Despite contextualization's acknowledged curricular relevance and integration within the classroom, a notable gap persists in the body of Chilean empirical research regarding this aspect.

Productive skills

Productive skills, encompassing both speaking and writing, imply that learners actively use the language, facilitating not only expression but also deeper comprehension and mastery of linguistic nuances, in contrast to the passive nature of reading and listening (Harmer, 2015). Given the perceived complexity of productive skills, they are approached in an integrated fashion, suggesting that they are complemented by their receptive counterparts rather than being taught in isolation (Harmer, 2015; Newton et al., 2018). This integrated-skill modality suggests that learners draw upon various skills as needed to communicate their ideas and thoughts effectively. The Chilean English curriculum aligns with integrated-skills planning to cultivate a holistic language learning experience, emphasizing not only linguistic competence but also the seamless integration of listening, speaking, reading, and writing skills (MINEDUC, 2016). While there is clear curricular evidence guiding the progression towards a comprehensive teaching practice, empirical research highlights the imperative for training institutions to intensify their efforts in equipping future teachers with effective ELT practices (Sato & Oyanedel, 2019) as these are directly connected with students’ learning experiences (Guerriero, 2017). The Chilean English curriculum is not far from these views since, for the development of both receptive and productive skills, educators are expected not only to display various teaching strategies but also to create pedagogical material tailored to the context of learners (MINEDUC, 2021).

Despite a lack of empirical evidence regarding the integration of receptive and productive language skills and how educators manage this balance within school environments, studies indicate that Chilean English as a Foreign Language (EFL) instructors tend to allocate more instructional time to receptive skills and decontextualized grammar instruction (Barahona, 2014; Sato & Oyanedel, 2019). This emphasis on receptive skills may contribute to the observed phenomenon wherein a significant portion of Chilean high school students fail to attain intermediate proficiency levels even when assessed solely on their receptive language abilities, with the majority (68%) identified as basic users of English (Agencia Calidad de la Educación, 2017).

Language-learning materials

Instructional materials or language-learning materials can be grasped as “anything which is deliberately used to increase the learners’ knowledge and/or experience of the language” (Tomlinson, 2011; p. 2[2]). In this regard, various stakeholders, such as writers, teachers, and learners can produce language-learning materials as long as these are created to facilitate language learning. Although materials development may appear simple, the process is far more complex as language-learning materials is not only a practical endeavor but also a field of studies. Therefore, the development of instructional materials necessitates a thorough evaluation to assess their impact on students' learning outcomes. As Tomlinson (2011) elucidates, mere student interest in the materials is insufficient; rather, these resources should enhance students' learning opportunities. Based on this, the proposed study not only centered on the creation of contextualized language-learning materials but also on assessing its efficacy in enhancing learners’ productive skills. Hence, this scenario signals the importance of exploring initiatives aimed at increasing EFL teachers’ learning materials that could enhance language learning skills. Therefore, the aim of the study was threefold: i) to document the development of a language-learning material, ii) to enhance the development of the material, and iii) to explore its efficacy in promoting productive skills in the English as a foreign language classroom.

Experience and Methodology

The methodological steps for this initiative were informed by Tomlinson's (2011) approach to developing instructional materials as well as the previous research experience of one of the researchers. Drawing from her prior experience working with phases and designing instructional materials (e.g, Vega-Abarzúa & Saavedra, 2022; Vega-Abarzúa et al., 2022), the researcher defined a series of stages necessary for the project’s development. In order to achieve this goal, the formation of a research team was needed. As such, three pre-service teachers from an EFL teaching program in Ñuble were recruited to collaborate in the development of a contextualized language learning material likely to enhance productive skills in the EFL classroom.

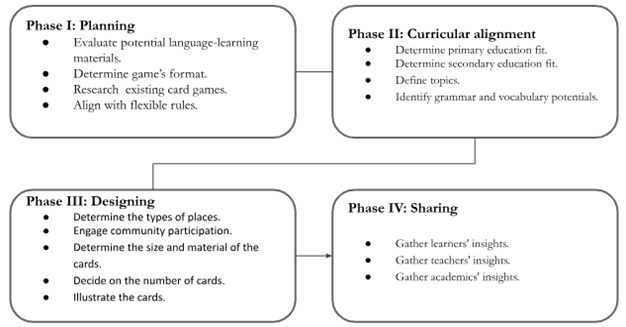

The development of our language-learning material involved four main stages: planning, curricular alignment, designing and sharing (see Figure 1). In the initial phase, the research team conducted an examination of potential language-learning materials. The team's objective was to develop a resource that could be utilized both physically and digitally. Drawing from scholarly literature, it became evident that card-based games offer numerous advantages, including increased interaction, engagement, enjoyment (Muslichatun, 2013; Zakaria et al., 2022) and opportunities for cross-curricular integration (Su et al., 2014). Consequently, significant time was allocated during the planning phase to explore existing card games and their defining characteristics. Given the aim of enhancing productive skills, the researchers opted for an elicitative resource. Tomlinson (2011) states that elicitative materials are designed to actively involve learners in language use. This appraisal aligned with the features of interactive games, as classified by Vossen (2004). The author explains that interactive games are characterized by their flexibility, allowing for adaptable rules that cater to diverse users’ interests and preferences. Consequently, our instructional material resulted in the development of a game with flexible rules, adaptable for various purposes, whether oral or written, aimed at stimulating productive skills.

Figure 1. Methodological phases in the development of the card game.

Source: Personal elaboration

In the second phase, researchers conducted a comprehensive review of English language study plans, programs as well as curricular orientations for primary and secondary education. This involved a systematic examination of global themes commonly addressed at these educational levels, such as food, transportation, the natural world, urban environments, and places. Subsequently, the researchers compiled these potential topics and assessed their relevance to students’ local context in Ñuble, Chile. Through a series of evaluations, each topic was scrutinized for its alignment with local culture and its potential to support instructional activities. Ultimately, the topic of places emerged as the most suitable choice, given Ñuble's diverse array of tourist attractions that could enrich the illustrations of the cards and fill them with details. This would allow practicing or reinforcing vocabulary words and grammatical structures pertinent to the English curriculum. With the topic defined, the researchers progressed to the subsequent stage: designing.

Initially, the design process for the card game posed a few complexities, yet as the researchers made progress, it became evident the numerous factors to be considered. The researchers began by examining the architecture of existing card games to inform their design choices. Through this investigation, it was determined that cards measuring 4 x 6 cm would be ideal for both primary and secondary school learners, facilitating comfortable manipulation. Additionally, to ensure durability and longevity, the cards were to be printed with a plastic cover to prevent folding or staining. The researchers also recognized the importance of the number of cards, as a limited quantity would hinder extended instructional practice.

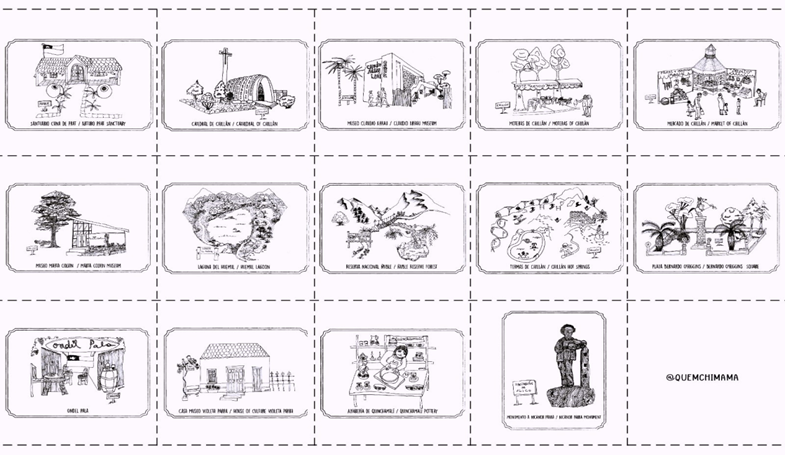

In response to this concern and to select suitable iconic places for the game, the research team decided to include the participation of the local community. To meet this end, ethical considerations were taken in to account, informing the participants about the project’s aim and their role through informed consent. The participants, selected via purposeful sampling, included 28 individuals among them teachers, students, and community members. These participants were asked to answer a single open-ended question, in which they identified three iconic places of the region, Ñuble. Participants’ answers were analyzed using content analysis, identifying 14 significant locations. Subsequently, one of the researchers illustrated each card, providing detailed context to facilitate speaking or writing activities (see Figure 2). The card game was named Places of Ñuble.

Figure 2. Places of Ñuble - card game overview.

Source: Personal elaboration

The final stage involved sharing the cards with learners, teachers, and academics to gather their insights on the game and to collect preliminary data on its efficacy in enhancing productive skills. These participants were selected using convenience sampling, and data were collected separately for each group and at different times. Informed consent was obtained, and participants were briefed on the project's objectives and the nature of the game. The insights from each group were collected differently as the researchers aimed to enhance the game and assess its efficacy in fostering productive skills.

The insights of two learner participants were gathered through observation and discussion. They participated in a guessing game using the card game, with one researcher explaining the game while the other recorded their actions in note fields. After the activity, the learners engaged in a brief discussion about their experience with the game. Their responses were documented in note fields and subsequently analyzed thematically.

Teachers' insights were collected during a professional development workshop facilitated by one of the researchers. This workshop, attended by approximately 30 in-service EFL teachers from diverse locations in Ñuble, provided an opportunity to delve deeper into the teachers’ perspectives on the card game and its potential to enhance productive skills. Through group discussions, the teachers explored activities they could implement with the card game. The researchers documented the teachers’ viewpoints using a focus group format, transcribing and thematically analyzing their opinions.

Finally, two academics contributed their perspectives on the card game through brief interviews. To ensure a diverse range of insights, the researchers interviewed both an English language teaching professor and a social studies professor specializing in heritage. The academics were queried about potential improvements to the game and its capacity to enhance productive skills.

Results

Learners’ insights

Through our observation and discussions with the participants, it became evident that the card game elicited motivation and fostered sustained interaction. Despite exhibiting shyness at the beginning of the game, both learners demonstrated the use of various grammatical structures and vocabulary items as their confidence grew throughout the activity. Although participants did not show language barriers or prolonged pauses, they made efforts to articulate more intricate thoughts. To overcome this, learners occasionally resorted to Spanish terms, simplified their ideas, and rephrased their discourse. Our observations also revealed an accented use of paralinguistic features, such as variations in intonation, facial expressions, and body language. We concluded that participants employed these strategies to maintain fluency and interaction in the game.

In addition to our observations, learners were asked about their experience with the game. Their feedback was highly positive, and the familiarity of the locations depicted in the game further motivated their participation. Both participants expressed a preference for using the cards in oral exercises, as it was the least utilized skill in their school contexts. In learners’ own words:

“it was fun because I was familiar with some of the places in the cards” (Participant 1)

“the game motivated me to say and ask many things” (Participant 2)

“the game should include more cards…it was fun and I loved the small details in the cards” (Participant 2)

“I wanted to describe some things.but I didn’t remember the words in English that is why I decided to describe other things so that my classmate could guess the place I was describing” (Participant 1)

“[using the card game at school] it could help my classmates to learn more words in a fun way” (Participant 1)

“I think I would prefer to use it [card game] orally because we do not get to say much in [English] classes” (Participant 2)

Teachers’ insights

All teacher participants agreed that the card game would not only help foster productive skills but also emphasized that learners would be motivated to use instructional materials tailored to the Chilean and regional context. Therefore, our preliminary findings not only signal the potential of contextualizing language-learning materials for improving language skills but also highlight their role in motivating learners in the EFL classroom.

Some teachers commented that learners in rural areas, who may sometimes be hesitant to use English, highly appreciate these types of contextualized resources. Others expressed enthusiasm for the idea of creating similar games within their own communities. Additionally, teachers noted that the game could be effectively utilized with young learners and adolescents, emphasizing its adaptability to various classroom activities and moments, even in assessments. Regarding implementation, they claimed that the card game can be used equally for oral and written practice. In terms of how they would use the card game, participants commented:

“I would use it [card game] as an ice-breaker activity” (Participant 10)

“I would use it [card game] in a written assessment in which learners read something related to a place, and then they have to select one place to write something about it” (Participant 12)

“I would use it [card game] to reinforce past tenses orally” (Participant 7)

“I would use it [card game] to have learners practice there is/are in a fun way” (Participant 23)

Academics’ insights

The two academics we interviewed emphasized that a contextualized material like our card game could enhance oral and/or written interaction in the EFL classroom. They both asserted that further research would be necessary to fully explore the impact of such materials on fostering language skills, as well as to identify best practices for their implementation in diverse educational settings. Additionally, they highlighted the importance of ongoing professional development for pre- and in- service teachers to effectively create and integrate these instructional materials into their teaching practices.

In addition to this discussion, the academics offered valuable insights. One suggested documenting the development process of the card game to inspire both pre-service and in-service teachers in creating language-learning materials for EFL learners. The other, an expert in heritage, recommended expanding the set of cards to include other important places in Ñuble. This recommendation aimed to enrich the game by incorporating significant heritage sites relevant to the region.

Discussion

Although the researchers started developing a card game without intending its documentation, the methodological procedures and insights from the informants signaled an importance for the English language teaching and learning community. Insights provided by the three groups of participants in this study indicated an appreciation for contextualization, with learners valuing the depiction of elements from their own contexts. These findings align with previous research emphasizing the benefits of connecting real-world scenarios to educational content (Chen & Wright, 2017; Jarideh & Kargar, 2016; Muslichatun, 2013; Zoghi & Mirzaei, 2014). For instance, while Muslichatum (2013) highlights the role of contextualization for learners' practice and improved speaking proficiency, Jarideh and Kargar (2016) underscore the importance of contextualization for learners' academic success.

Furthermore, our findings reveal that learner participants actively engaged in productive skills, particularly speaking, which aligns with the findings of Muslichatun (2013). Their card-game study focused not only on vocabulary learning but also on exploring learners’ speaking proficiency, signaling a positive impact between the game-based learning and productive skills.

Insights from teacher participants further emphasized the potential of our card game for enhancing productive skills, with suggested activities aligning well with oral and written tasks. These findings lead us to conclude that card games, in addition to strengthening vocabulary and grammatical development (Razali et al., 2017; Sung & Ching, 2012; Zakaria et al., 2022), can also foster speaking and writing skills (Limantoro, 2018; Muslichatun, 2013; Zakaria et al., 2022). However, further research is necessary to explore the effectiveness of card games in fostering productive skills and to identify best practices for their implementation in educational settings.

Additionally, contextualized language-learning activities appear to be closely linked with motivation. Both learner and teacher participants addressed this aspect, with learners expressing enjoyment of the card game activity and teachers anticipating their learners' enthusiasm while using the cards. This observation aligns with findings from previous studies, where learners reported higher levels of engagement towards game-based learning (Muslichatun, 2013; Sung & Ching, 2012; Zakaria et al., 2022).

Conclusion

It is important to note that the experience in developing and preliminary exploring the efficacy of this game revealed the importance of theoretical aspects informed mainly by Tomlinson (2011) to ensure that the game satisfies the learning needs of students. In line with this, the methodological steps in developing instructional material should align with curricular standards to ensure that the material effectively addresses the learning objectives and requirements specified in the curriculum. Therefore, our study and experience can contribute to teacher education programs as future teacher generations are expected to create instructional materials to facilitate language learning (MINEDUC, 2021).

In this study it was possible to learn that developing this type of language-learning games requires incorporating expertise beyond English language teaching, emphasizing the need for a multidisciplinary team in creating game-based materials, specifically if they contain culturally relevant aspects. This crucial detail was overlooked in this study as the researchers solely focused on collecting data from English language learning communities during the development of the cards. This aspect became evident when one of our academic participants identified local places that were relevant but not addressed in the game.

Future ELT research could further investigate the effectiveness of this card game or similar language-learning materials in improving productive skills using alternative methods, longer durations, and diverse school settings.

Conflicts of interest

The authors of this study claim that they do not have any conflicts of interest to declare.

References

Agencia Calidad de la Educación (2017, March 27). Informe de resultados estudio nacional de inglés 2017. https://archivos.agenciaeducacion.cl/Informe_Estudio_Nacional_Ingles_III.pdf

Baker, E. D.; Hope, L. & Karandjeff, K. (2009). Contextualized teaching & learning: A promising approach for basic skills instruction. Research and Planning Group for California Community Colleges (RP Group). https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED521932.pdf

Barahona, M. (2014). Pre-service teachers’ beliefs in the activity of learning to teach English in the Chilean context. Cultural-Historical Psychology, 10(2), 116-122. https://psyjournals.ru/journals/chp/archive/chp_2014_n2.pdf#page=116

Chen, P. G.; Liu, E. Z. F.; Lin, C. H.; Chang, W. L.; Hsin, T. H. & Shih, R. C. (2012). Developing an education card game for science learning in primary education. In: 2012 IEEE Fourth International Conference On Digital Game And Intelligent Toy Enhanced Learning (pp. 236-240). IEEE. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/6185626

Chen, M. P.; Wang, L. C.; Zou, D.; Lin, S. Y. & Xie, H. (2019). Effects of caption and gender on junior high students’ EFL learning from iMap-enhanced contextualized learning. Computers & Education, 140, 103602. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.103602

Chen, M. P.; Wang, L. C.; Zou, D.; Lin, S. Y.; Xie, H. & Tsai, C. C. (2022). Effects of captions and English proficiency on learning effectiveness, motivation and attitude in augmented-reality-enhanced theme-based contextualized EFL learning. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 35(3), 381-411. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2019.1704787

Chen, Q., & Wright, C. (2017). Contextualization and authenticity in TBLT: Voices from Chinese classrooms. Language Teaching Research, 21(4), 517-538. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168816639985

Correa, R.; Lara, E.; Pino, P. & Vera, T. (2017). Relationship between group seating arrangement in the classroom and student participation in speaking activities in EFL classes at a secondary school in Chile. Folios, (45), 145-158. http://www.scielo.org.co/pdf/folios/n45/n45a11.pdf

Ellis, R. (1994). The study of second language acquisition. Oxford.

Guerriero, S. (2017). Pedagogical Knowledge and the Changing Nature of the Teaching Profession. OECD Publishing.

Harmer. J. (2015). The practice of English language teaching (3rd ed.). Pearson Longman.

Humaini, A. (2018). Experimental research: the effectiveness of card game learning media in learning shorof. Jurnal Al Bayan: Jurnal Jurusan Pendidikan Bahasa Arab, 10(2), 295-307. http://download.garuda.kemdikbud.go.id/article.php?article=928319&val=5890&title=Experimental%20Research%20The%20Effectiveness%20of%20Card%20Game%20Learning%20Media%20in%20Learning%20Shorof

Jarideh, F. & Kargar, A. A. (2016). Investigating the Impact of the Degree of Contextualization on Iranian Intermediate EFL Learners’ Reading and Listening Tests Performance. English Language Teaching, 2, 11-33. https://jmrels.journals.ikiu.ac.ir/article_805_6a2de5335003d021cdc00910b38ec819.pdf

Johnson, E. B. (2002). Contextual teaching and learning: What it is and why it's here to stay. Corwin Press.

Larsen-Freeman, D. (2011). Techniques and principles in language teaching. Oxford University Press.

Limantoro, S. W. (2018). Developing word-card games to improve English writing. PUPIL: International Journal of Teaching, Education and Learning, 2(3), 38-54. https://dx.doi.org/10.20319/pijtel.2018.23.3854

Mazzeo, C. (2008). Supporting student success at California community colleges: A white paper. Prepared for the Bay Area Workforce Funding Collaborative Career by the Career Ladders Project for California Community Colleges.

Ministerio de Educación (2016). Idioma extranjero inglés [English as a foreign language]. Curriculum Nacional.

https://www.curriculumnacional.cl/614/w3-propertyvalue-52050.html

Ministerio de Educación (2021). Estándares de la profesión docente. Carreras de pedagogía en inglés. [Teaching standards for English education programs]. https://estandaresdocentes.mineduc.cl/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/ingles.pdf

Muslichatun, I. (2013). Improving the students’ speaking practice in describing people by using contextualized card game. Language Circle: Journal of Language and Literature, 8(1), 23-34. https://doi.org/10.15294/lc.v8i1.3226

Newton, J. M.; Ferris, D. R.;Goh, C. C.; Grabe, W.; Stoller, F. L. & Vandergrift, L. (2018). Teaching English to second language learners in academic contexts: Reading, writing, listening, and speaking. Routledge.

Partnership 21 (2015). P21 Partnership for 21st Century Learning. http://www.p21.org/storage/documents/docs/P21_Framework_Definitions_New_ Logo_2015.pdf

Razali, W. N.; Amin, M. N.; Kudus, N. V. & Musa, M. K. (2017). Using card game to improve vocabulary retention: A preliminary study. International Academic Research Journal of Social Science, 3(1), 30-36. https://www.iarjournal.com/wp-content/uploads/IARJSS2017_1_30-36.pdf

Rivet, A. & Krajcik, J. (2008). Contextualizing Instruction: Leveraging Students’ prior knowledge and experiences to foster understanding of middle school science. Wiley InterScience. https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/bitstream/handle/2027.42/57510/20203_ftp.pdf?sequence=1

Roberts, T. A.; Vadasy, P. F. & Sanders, E. A. (2020). Preschool instruction in letter names and sounds: Does contextualized or decontextualized instruction matter? Reading Research Quarterly, 55(4), 573-600. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.284

Sato, M. & Oyanedel, J. C. (2019). “I think that is a better way to teach but…”: EFL teachers’ conflicting beliefs about grammar teaching. System, 84, 110-122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2019.06.005

Sticht, T. (2000). Functional context education: Making learning relevant. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED480397.pdf

Su, T.; Cheng, M. T. & Lin, S. H. (2014). Investigating the effectiveness of an educational card game for learning how human immunology is regulated. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 13(3), 504-515. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.13-10-0197

Sung, H. & Ching, G. (2012). A case study on the potentials of card game-assisted learning. International Journal of Research Studies in Educational Technology, 1(1), 25-31. https://doi.org/10.5861/ijrset.2012.v1i1.64

Tomlinson, B. (2011). Materials development in language learning (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Vega-Abarzúa, J. & Pleguezuelos Saavedra, C. (2022). Aprendizaje Basado en Proyectos: Experiencia interdisciplinar entre inglés y Diseño Gráfico en pregrado. Revista de Estudios y Experiencias en Educación, 21(46), 416-428. http://dx.doi.org/10.21703/0718-5162.v21.n46.2022.023

Vega-Abarzúa, J.; Pastene-Fuentes, J.; Pastene-Fuentes, C.; Ortega-Jiménez, C. & Castillo-Rodríguez, T. (2022). Collaborative learning and classroom engagement: A pedagogical experience in an EFL Chilean context. English Language Teaching Educational Journal, 5(1), 60-74. http://dx.doi.org/10.12928/eltej.v5i1.5822

Vossen, D. P. (2004). The nature and classification of games. Avante, 10(1). https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=f51f6b4bae3bed7cfe78196644ccbec867c1ab4b

Zakaria, N.; Anuar, N. A. K.; Jasman, N. H.; Mokhtar, M. I. & Ibrahim, N. (2022). Learning grammar using a card game. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 12(2), 464-472. http://dx.doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v12-i2/12259

Zoghi, M. & Mirzaei, M. (2014). A comparative study of textual and visual contextualization on Iranian EFL learners' vocabulary learning. International Journal of Basic and Applied Science, 2(3), 31-40. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/A-Comparative-Study-of-Textual-and-Visual-on-EFL-Zoghi-Mirzaei/00f3bafad732296b310fa6f789597178c0fdcd8b